A bunch of years ago, when I was twenty, I left the church I’d grown up in, where I’d been trained to think of God as God-the-Father: a literal, corporeal, male parent. I couldn’t reconcile that mythic system with the complexity of the rest of the world. So I bowed out, and I started rebuilding my thoughts about religion from scratch. Two ideas had strength for me. The first was, Follow your bliss because no one’s going to do it for you (thank you, Joe Campbell). The second was, You’re always allowed to change your mind.

But what was that supposed to mean — follow your bliss? I wasn’t sure what my bliss was, much less how to follow it. I decided to substitute a different word: fascination. I knew what it meant to feel the fizz of interest, and to attend closely to the people-places-parties that elicited that electricity, so I went with that.

Then I encountered complexity theory, a branch of science that studies how complicated, increasingly ordered systems emerge in the universe. These phenomena seem to thumb their collective nose at the second law of thermodynamics, which states that disorder, or entropy, always increases. Complexity theory describes the magic that happens at the edges of order and disorder, when organization gets a little chaotic, and chaos gets a little organized, and all of a sudden newness bursts forth: new planets, species, organisms, art. In his book Reinventing the Sacred, the complexity theorist Stuart Kauffman writes that “a wondrous radical creativity without a supernatural Creator” is an attribute of the universe. “God,” he says, “is our chosen name for the ceaseless creativity in the natural universe, biosphere, and human cultures.”

When I read that, my whole body seemed to ring. I rose up off the sofa, book in one hand and a cup of tea in the other. The tea began flying out of the mug, but time slowed down so much that I was able to circle the cup around the moving liquid and gather it back, still thrilling to this idea: creativity inheres in the universe. Not just in Mozart, not just in Shakespeare. In the universe, meaning everything, meaning all of us. God is that which creates, whenever creation occurs.

I was thinking about all this, and I asked my bbf (beloved boyfriend) what he thought God was. Without missing a beat, Michael said, “The zingy-zangy around everything.” See why I love him so much? He gets it.

And doesn’t “zingy-zangy” sound like bliss, like the sizzle and spark of fascination, like the fire and fuel of passion? Following bliss is the same as following the zingy-zangy, which is God, which means your bliss is God is fascination is passion is the creativity which gives rise to the emergence of new complexity.

The times I’ve experienced the zingy-zangy most profoundly have had a bodily sensation of vastness and openness, with feelings of awe, wonder, and love that extend past all horizons in all directions. These moments happen at the edges of order and disorder, in psychological places outside judgments of good and bad, right and wrong — places I experience as amazing. Or heartbreaking. Or beautiful. Places defined by intensity.

A felt sense of vast possibility pulses in the infinite space at the invisible edge, outside and all around the ordered systems of our lives. Our complex material bodies and complex, seemingly immaterial consciousness cooperate in even more complex ways that still elude understanding. Who knows what could happen when our ordered selves encounter the disorder of death? Complexity theory suggests that it could be something new, meaning we can’t predict it and it could be different for everyone. It could feel like what religions sometimes refer to as heaven.

A felt sense of vast possibility pulses in the infinite space at the invisible edge, outside and all around the ordered systems of our lives. Our complex material bodies and complex, seemingly immaterial consciousness cooperate in even more complex ways that still elude understanding. Who knows what could happen when our ordered selves encounter the disorder of death? Complexity theory suggests that it could be something new, meaning we can’t predict it and it could be different for everyone. It could feel like what religions sometimes refer to as heaven.

Last month my graduate coursework ended, a three-year marathon with no breaks between quarters. The day after my last class, I woke up late and lay in bed for an hour, feeling leaden and empty, drained of emotion and motivation. I hovered at the edge of the ordered system of the previous three years, and the disorder of the unstructured future. Then ideas about this blog post started rolling around in my mind like billiard balls. Two of them connected with a satisfying thwack, and I felt the first stirrings of vitality return, a small spring of interest, energy, enthusiasm — a word whose root means “God within,” which therefore also means bliss – fascination – creativity – passion. The great zingy-zangy.

Another phenomenon that emerges in this zingy-zangy universe is agency. In other words, you get to choose how to engage with the world, with bliss, with creativity, with the same zingy-zangy that gave rise to agency in the first place. And you’re always allowed to change your mind.

As expressions of the zingy-zangy — children of it, so to speak — we are invited to play with it. All it takes is the merest time-out, a tiny break in the hypnosis of thought, a sliver of silence to listen for tingle, to feel for the fizz, to savor the sparkle that infuses your being.

Shh… there it is. Do you feel it? Open to it. Sink into it. Let it have you. Now smile. Feel the shimmer strengthen? Feel it twinkle? That’s your bliss. That’s creativity. It’s the great zingy-zangy smiling back.

![Pentheus Being Torn by Maenads, By WolfgangRieger [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://joannagardner.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Pompeii_-_Casa_dei_Vettii_-_Pentheus-1-994x1024.jpg)

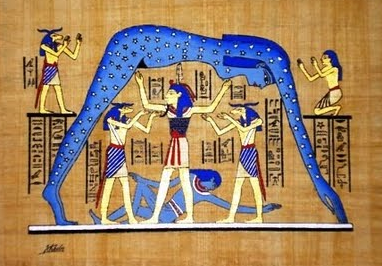

Night goddesses don’t ask for much, but they do insist on visiting. Actually, we visit them, every evening when our zip code rolls away from the sun and out to face the reaches of space. Night holds the dark half of the planet in the palms of Her cupped hands, at all times. She’s always there as we move into, through, and out of Her domain. When in Night, we’re in all the way, and Night is all the way in us. It’s Night outside, Night in the kitchen, Night in the bedroom. Night within blood vessels, in the synapses between neurons, inside every cell membrane in all of our bodies.

Night goddesses don’t ask for much, but they do insist on visiting. Actually, we visit them, every evening when our zip code rolls away from the sun and out to face the reaches of space. Night holds the dark half of the planet in the palms of Her cupped hands, at all times. She’s always there as we move into, through, and out of Her domain. When in Night, we’re in all the way, and Night is all the way in us. It’s Night outside, Night in the kitchen, Night in the bedroom. Night within blood vessels, in the synapses between neurons, inside every cell membrane in all of our bodies.

![Antonio da Correggio, Mercury in "The Education of Eros" [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://joannagardner.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/1024px-Correggio_014-245x300.jpg)

Mythologically guns belong first and foremost to the thunder gods. Zeus in Greece, Indra in India, Shango in African traditions — they all throw lightning bolts really fast, really loud, bolts that can kill you before you know what happened. But because these gods are kings, asking for a gun for Mother’s Day mixes mythic metaphors. When the King usurps the festival of the Mother, goddesses object. Demeter in Greece, Durga in India, and Yemaya in Africa all have different interests than the lightning gods.

Mythologically guns belong first and foremost to the thunder gods. Zeus in Greece, Indra in India, Shango in African traditions — they all throw lightning bolts really fast, really loud, bolts that can kill you before you know what happened. But because these gods are kings, asking for a gun for Mother’s Day mixes mythic metaphors. When the King usurps the festival of the Mother, goddesses object. Demeter in Greece, Durga in India, and Yemaya in Africa all have different interests than the lightning gods.

He bellowed for the rest of the Olympians to come witness this travesty. The goddesses declined, giving a self-righteous roll of their ravishing eyes. The gods, on the other hand, dropped everything to race over to Hephaestus’s palace and laugh at the beautiful lovers caught in that glittering net.

He bellowed for the rest of the Olympians to come witness this travesty. The goddesses declined, giving a self-righteous roll of their ravishing eyes. The gods, on the other hand, dropped everything to race over to Hephaestus’s palace and laugh at the beautiful lovers caught in that glittering net. The myth gives us an image of one partner treating the other like a possession, demanding fidelity on principle alone. Love — aka Aphrodite — considers this preposterous. Love knows that love comes first. Love means first and foremost loving the beloved, second and second-most wanting the beloved. If Hephaestus loved Aphrodite, he would not have married her, much less expected fidelity, because he knew she wanted Ares. Ares, by the way, never makes petulant demands. He’s too busy going watery in his magnificent knees every time he sniffs her skin, swooning in dizzy joy at her voice, staggering around in a dazed kind of gratitude that she exists at all.

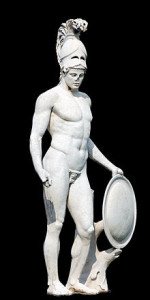

The myth gives us an image of one partner treating the other like a possession, demanding fidelity on principle alone. Love — aka Aphrodite — considers this preposterous. Love knows that love comes first. Love means first and foremost loving the beloved, second and second-most wanting the beloved. If Hephaestus loved Aphrodite, he would not have married her, much less expected fidelity, because he knew she wanted Ares. Ares, by the way, never makes petulant demands. He’s too busy going watery in his magnificent knees every time he sniffs her skin, swooning in dizzy joy at her voice, staggering around in a dazed kind of gratitude that she exists at all.  Remember how incredibly beefcake Bruce was? He ran fast and he ran far, he jumped like crazy. He hurled beastly heavy things then roared with exultation. He demonstrated all the attributes of a superb foot soldier. In winning gold for the United States, he wore our national image of Ares, the Greek god of war. He let us imagine ourselves as the world’s greatest, strongest, fastest, best. His muscle was our might. At the same time, his youth was our immaturity. His soul roiled with secret misery. So did ours.

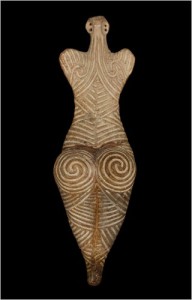

Remember how incredibly beefcake Bruce was? He ran fast and he ran far, he jumped like crazy. He hurled beastly heavy things then roared with exultation. He demonstrated all the attributes of a superb foot soldier. In winning gold for the United States, he wore our national image of Ares, the Greek god of war. He let us imagine ourselves as the world’s greatest, strongest, fastest, best. His muscle was our might. At the same time, his youth was our immaturity. His soul roiled with secret misery. So did ours.  The story also shows an image of a woman with decades of lived experience as a male athlete. Caitlyn carries that in her muscle memory, all the more powerfully because of the power of those muscles. She walks with the bodily knowledge of life and sex and sports as a champion man in the eyes of society. She now gathers into those same muscles the experience of being a woman in the eyes of society. Because of that, she lives and breathes the union of opposites. She joins Cinderella and Prince Charming within herself. She is Aphrodite and Ares, both at once. The Goddess and her Consort. Caitlyn offers us an image of soul totality, of wholeness. If her soul can do that, ours can too.

The story also shows an image of a woman with decades of lived experience as a male athlete. Caitlyn carries that in her muscle memory, all the more powerfully because of the power of those muscles. She walks with the bodily knowledge of life and sex and sports as a champion man in the eyes of society. She now gathers into those same muscles the experience of being a woman in the eyes of society. Because of that, she lives and breathes the union of opposites. She joins Cinderella and Prince Charming within herself. She is Aphrodite and Ares, both at once. The Goddess and her Consort. Caitlyn offers us an image of soul totality, of wholeness. If her soul can do that, ours can too. Cinderella stories imagine the soul emerging from that underworld and shining in its own authenticity. They celebrate the beauty of the true self finding its place in the world. Caitlyn Jenner seems to be doing exactly that. She transformed Olympic gold into a golden dress. She acts as an agent of The Goddess. In that capacity, she advocates for the rights and respect due to the transgender community, and for the inner lives of everyone. Her Goddess messages have to do with authenticity, the fluidity of external identity, our vast possibilities for transformation, and polytheistic acceptance and joy rather than monotheistic judgment. She presents us each with the ultimate mythological questions: What is your authenticity? What does your soul want to express? What transformations of body and consciousness would you embark upon, given that you, like Caitlyn, have the strength of the warrior and the courage of the lover?

Cinderella stories imagine the soul emerging from that underworld and shining in its own authenticity. They celebrate the beauty of the true self finding its place in the world. Caitlyn Jenner seems to be doing exactly that. She transformed Olympic gold into a golden dress. She acts as an agent of The Goddess. In that capacity, she advocates for the rights and respect due to the transgender community, and for the inner lives of everyone. Her Goddess messages have to do with authenticity, the fluidity of external identity, our vast possibilities for transformation, and polytheistic acceptance and joy rather than monotheistic judgment. She presents us each with the ultimate mythological questions: What is your authenticity? What does your soul want to express? What transformations of body and consciousness would you embark upon, given that you, like Caitlyn, have the strength of the warrior and the courage of the lover?