What’s a magical realist?

Being a magical realist means taking reality seriously while looking for its innate magic. It means discerning between fiction and nonfiction, truth and lies while staying open to the mystery of existence.

One way to define magic is the appearance of things no one saw coming, or surprises. For example, consider the magical yet utterly real nature of love, beauty, creativity, dreams, and imagination. In my view, these wonders prove reality is magical and therefore magic is real.

For me, the genre of magical realism captures more of reality than realism alone. From the time I was little, it was the strange parts of stories that resonated most powerfully for me. Impossible characters and events often felt more true than the mundane in a way I couldn’t explain. I didn’t understand that effect until I studied mythology. Then I realized I had been responding to the metaphorical truth of those moments. They were metaphorical whispers of the reality of the sacred, or the divine. They said Look! There more to the world than meets the eye. Pay attention!

New course starts May 27

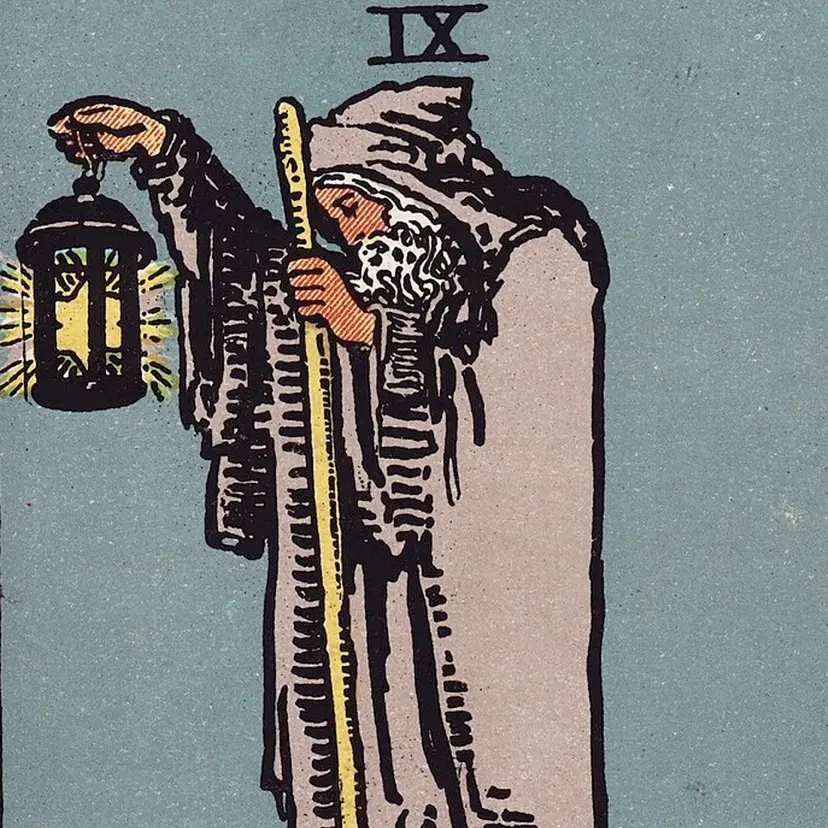

I’ll be leading two sessions in an upcoming course from Roundtable.org by the 92nd Street Y in New York called Mythic Archetypes of Experience: Wise One, Healer, Sovereign, Shadow.

The class will have four monthly sessions beginning on May 27, and my sessions will be about the Wise One and the Sovereign archetypes. Join us to explore symbols of the knowledge and insights gained in adulthood!

New MythBlast: Wisdom and Wonder in Bless Me, Ultima

It was a joy to write a MythBlast essay for the Joseph Campbell Foundation about the film Bless Me, Ultima. The movie is based on one of my favorite novels of all time, also called Bless Me, Ultima, by Rudolfo Anaya.

When the book first came out, everyone said Oh this is a classic of New Mexican literature! Then they said it was a classic of Chicano literature, then they said Ok, ok, it’s a classic of American literature. At this point maybe we can just say it’s a phenomenal book, weaving together New Mexico’s beauties, complexities, and cultures—Indigenous, Spanish, and Anglo—in the character of Ultima, a curandera (folk healer) and wise woman whose powers defy rational explanation.

The Practice of Enchantment

Thank you to the Joseph Campbell Foundation for publishing my book, The Practice of Enchantment: MythBlast Essays, 2020-2024. Inspired by the work of Joseph Campbell, these essays are about how myth enlivens and enchants everyday life.

My latest blog posts

- Viewer’s Guide to the Superman Preview, FAQQ: Really? A comic book movie? Haven’t you seen the news lately? I think we have more important matters to discuss. A: It’s because of the news that we need … Continue reading Viewer’s Guide to the Superman Preview, FAQ

- Americans in NormandyLast fall I traveled from Normandy, France, to Paris in the back of a bus with a view out over the French countryside. The green fields and hedges looked peaceful … Continue reading Americans in Normandy

- Practicing EnchantmentI am so grateful to the Joseph Campbell Foundation for publishing my book, The Practice of Enchantment: MythBlast Essays, 2020-2024. Thank you, JCF! This book is a collection of fourteen … Continue reading Practicing Enchantment

Surprise! A newsletter!

Once a month I send an email to subscribers such as yourself with recommendations for books and articles about myth, creativity, and creative inspiration, plus my upcoming courses, publications, and events. If that sounds like your cuppa tea or coffee or maybe hot cocoa, please subscribe!

To subscribe, fill out this form:

For information about my privacy practices, visit this site’s privacy page.